Ghanaian movie posters are a lie that tells the truth, the way all great hustles do. They promise a film, but what they really deliver is a fever dream of the film, painted on the skin of yesterday’s grain and carried from town to town like a wandering oracle with bad juju and better stories.

They began, or at least came to be called what they are, in the mid‑1980s, when the cassette and the VCR slithered into West Africa with all the patient venom of a new religion. In Ghana, where the infrastructure of official culture had never been much more than a rumor, these machines birthed the mobile cinemas: traveling video clubs that would haul a TV, a generator, and a box of tapes into some open courtyard, rig a few benches, and transubstantiate the night into flickering blood and light. For this, you needed an image strong enough to pull a crowd off the street. You needed a banner, a threat, a promise.

So the sign painters got to work. Not the gallery darlings or state‑approved visionaries, but the guys who painted bar signs, barber-shop saints, and “NO URINATING HERE BY ORDER” on crumbling walls. They took recycled flour‑sack canvas—the same material that had hauled grain through ports and borders—and gave it a second life as cheap immortality. The sacks were split, stitched, and stretched. On this rough skin, they conjured posters for Hollywood, Bollywood, and home‑grown films they had sometimes never actually seen. A battered VHS sleeve, a rumor, a title, a half‑remembered lobby card from some foreign magazine—this was enough.

From the mid‑’80s through the late ’90s, that so‑called Golden Age, the traveling cinemas and their paintings roamed like a circus of ghosts. The economy was lean; the power went out when it felt like it; home video was still a luxury, not a default. This was the crack in the world where these things thrived. Once cheap digital printing spread and televisions settled into living rooms like permanent lodgers, the posters became needless, then obsolete, then rare—like the molted skins of some species nobody bothered to catalogue until it was almost gone.

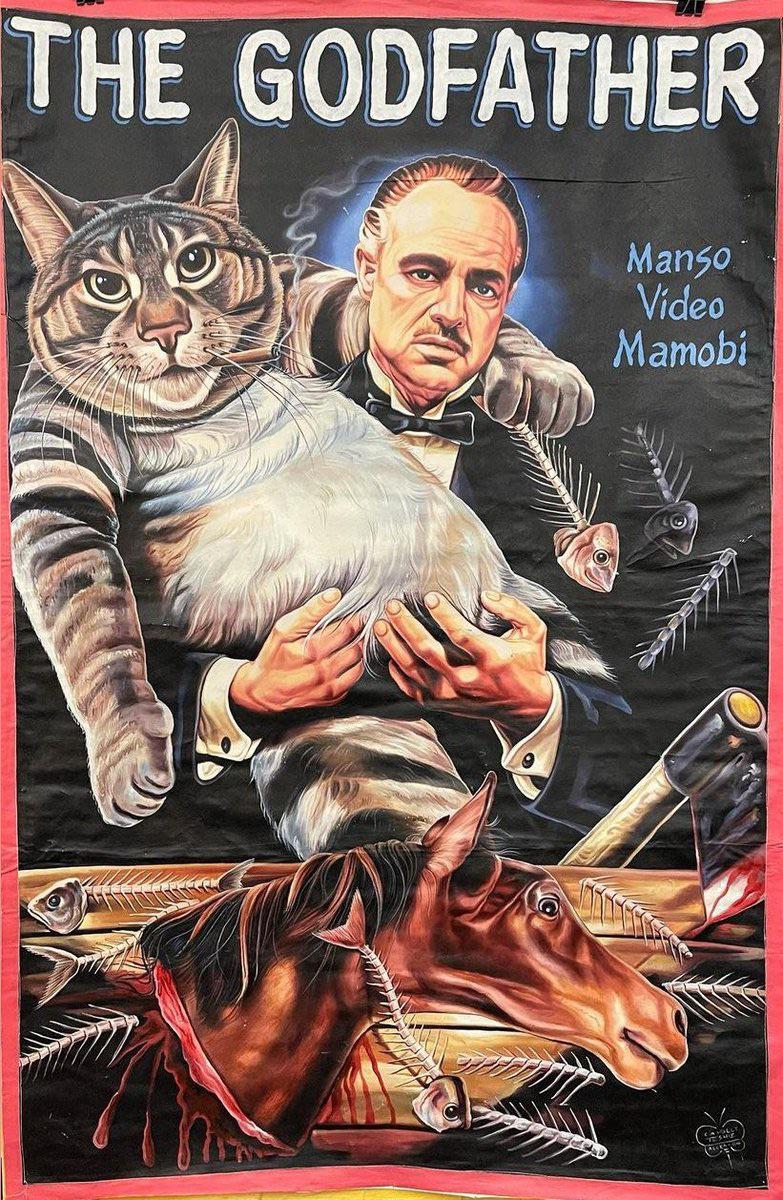

The style was born out of necessity and delirium. You could not afford subtlety when your marketplace was dust and noise and the competition was the dull grind of daily life. So the painters gave you what the film could not, or would not: muscles that outgrew the body like tumors of strength, bullets the size of coconuts, blood blooming in impossible arcs. Faces became masks of rage or terror. Monsters crawled in from nowhere—no relation to the script, just freeloaders from the painter’s own private hell. The American cop drama got a demon with goat horns. The family comedy sprouted machetes and fanged clowns. If the film was a whisper, the poster was a scream.

The geography carved its own styles into the work. Down on the coast, around Accra, some painters grew meticulous and dense, packing in detail until the canvas felt like an overstocked altar. Names like Joe Mensah and Leonardo floated up from those streets, men who could turn the cheap blue of hardware‑store paint into something close to revelation. In Kumasi and the Ashanti hinterlands, a smoother, almost airbrushed approach took hold: sleek gradients, bold silhouettes, the violence lacquered like a hot rod. It was still insanity, but with the edges sanded, the nightmare given chrome.

The painters were rarely treated as artists at the time. They were craftsmen, hustlers, hired hands. They did bar signs by morning, film posters by afternoon, whatever paid enough to keep paint on the brush. The idea that their work would someday be freighted across oceans, hung in white‑walled museums, and ogled by people who owned more books about “outsider art” than chairs—that would have been a joke, and not a particularly funny one.

But the West has a talent for delayed discovery, for suddenly deciding that some thing it ignored yesterday is now priceless because the right kind of eyes have seen it. So collectors, curators, and cultural middlemen began to orbit Ghana. A Los Angeles gallerist would find himself in some dingy hall, pointing at a torn canvas of a liquefied Jean‑Claude Van Damme with extra heads. A Chicago outfit would start buying stacks of old posters, rescuing them from rot, termites, and the rain. These people gave the works titles, dates, provenance. They turned the anonymous sign painter into “D.A. Jasper” or “Heavy J,” into someone who could be footnoted, catalogued, insured. The gutters got their saints.

The old canvases from the Golden Age now move through the world as artifacts. They are tagged as African popular art, “low‑brow,” or some other taxonomy meant to excuse the fact that they make most polite contemporary painting look like hotel wallpaper. They hang in institutions that once would have turned up their nose at anything that smelled this much like life. Prices climb. A poster that once screamed in the rain outside a cinder‑block hall in Tema now purrs behind glass, asking a five‑figure ransom from a collector who has never watched a pirated tape projected onto a cracked wall.

And because demand never sleeps, a second wave rose up. The same, or younger, painters now take commissions from overseas—emails sent from Brooklyn, Berlin, Melbourne—to reimagine films from every corner of the culture. New canvases appear for old horror flicks, for cult action tapes, for big‑studio comedies that were never grimy enough for their own good. A Ghanaian artist who once painted a bootleg Schwarzenegger from a tiny photo is now being asked to do a custom poster of some American’s cat as a chainsaw‑wielding warlord. The money is better. The work is cleaner. The strange holiness is still there, if you know how to look.

There is, out in the world, a small constellation of people and places that act as keepers of this fire. A gallery in Chicago dedicates itself to these posters, working with a handful of painters in and around Accra, commissioning fresh canvases and shipping them to people whose walls have been dead too long. On the West Coast, a Los Angeles gallery that once trudged through Ghana in the ’80s and ’90s now sells the field‑collected pieces from that era like relics—the chipped, scarred survivors of a vanished economy. Online shops in Europe and Africa specialize in these things, listing the film titles, the artists, the dimensions, the price in patient, measured currency. Behind each sterile product photo is the smell of turpentine and diesel, the sound of a generator coughing toward night.

The internet, ever hungry, turned them into shareable ephemera and altar pieces at the same time. Social feeds dedicated to “epic Ghana movie posters” scroll out a litany of screaming faces and flayed torsos, each new canvas trying to out‑sin the last. To the casual eye, they’re good for a laugh: ha ha, look at this insane Rambo with eight bazookas and Satan’s head in his fist. But stare a little longer and some other shape emerges. You begin to see what it means to take the global junk of VHS culture and feed it back to the world as folk religion.

Buying one is not just an act of consumption; it is a kind of screwed‑up communion. You are paying for a piece of somebody else’s local history, a relic of nights where cinema wasn’t a thing you streamed on a couch but a ritual that dragged you out under the open sky. The better dealers know this, and they stage the whole affair with a sober conscience: they separate originals from prints; they tell you when a piece is vintage, torn from the old mobile‑cinema days, and when it’s fresh paint destined from birth for a climate‑controlled apartment. They explain how much of the money finds its way back to the painter, the guy still standing in a cramped Accra workshop, painting some Hollywood undead nightmare onto the ghost of a flour sack.

Somewhere, a kid in Ghana is seeing these posters not as work, not as hustle, but as a kind of inheritance. He sees the old canvases—creased, bruised, magnificent—and the new commissions, crisp and export‑ready, and understands that the distance between them is the distance between the street and the museum. He might never own a camera. He might never make a film. But he can take the flickering trash of global cinema and resurrect it in paint, bigger, bloodier, stranger than it ever deserved to be.

Ghanaian movie posters are not about accuracy. They are about appetite. They show the film we wished we were getting, the violence and ecstasy and lunatic grandeur that the tape could never deliver on a small, buzzing screen. The world took them, as it always does, and filed them under genres and markets and academic readings. But in the end, they remain what they always were: rough, radiant lies painted on the backs of old flour sacks, promising you a night you might not walk away from—and meaning it.

Where to buy and sell Ghanian Movie Posters

You can buy Ghana hand-painted movie posters through a few specialist galleries and online marketplaces, and you can sell them either via those same galleries or collector-focused platforms and groups.

Deadly Prey Gallery (Chicago) focuses specifically on original hand-painted Ghanaian movie posters, works directly with artists in and around Accra, and sells originals, commissions, and prints online. deadlypreygallery.com

Ernie Wolfe Gallery (Los Angeles) maintains one of the largest collections of “Golden Age” Ghana posters from roughly 1985–1999 and sells them as fine art. erniewolfegallery.com

TribalGH is an online shop based in Ghana that offers a rotating inventory of authenticated hand-painted movie posters at gallery-level price. tribalgh.com